Black-necked Grebe (Podiceps nigricollis)

Black-necked Grebe © Sue & Andy Tranter

Cheshire featured strongly in the 20th century history of Black-necked Grebes in the UK, so it is fitting that, during the period of this survey, Cheshire held the largest colony of Black-necked Grebes in the country (Holling et al 2007).

As well as the colony at the Woolston Eyes SSSI, which includes parts of three tetrads (SJ68J/ N/ P), during this Atlas survey pairs with young were seen at the Moore Nature Reserve (SJ58X/ Y), and single birds stayed at three other sites in the northern part of the county. Despite thorough survey work during this Atlas, no Black-necked Grebes were found in the Delamere area, the species’ favoured location during earlier colonisation of the county in the 1940s, 1950s and 1980s: Blakemere, with its large gull colony, appears to be eminently suitable, but the birds obviously think otherwise. A prominent feature of most, but not all, successful Black-necked Grebe colonies is their association with nesting Black-headed Gulls, which must give some measure of protection from aerial predators. On the other hand, such a congregation of easy prey might attract other killers such as mink.

Their favoured habitat is shallow, eutrophic waters, usually with extensive fringing vegetation and often floating aquatic plants, and a site preferably sheltered from strong winds. Black-necked Grebes mostly eat insects and their larvae, occasionally other invertebrates or small fish, mostly caught by diving for 20 or 30 seconds, but some of which they gather with their charming habit of skimming the water surface and turning their head from side to side, using their slightly upturned bill in the manner of an Avocet.

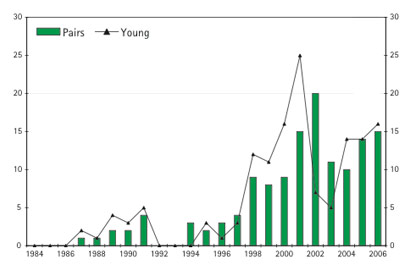

Black-necked Grebe breeding numbers at Woolston.

After a typically elaborate ‘grebe-type’ display, pairing seems to be rapid and breeding at Woolston is often much earlier than normally recorded elsewhere. The first chicks are usually seen in late May, with most pairs apparently rearing two young, and one adult looking after each chick; the stripey-plumaged youngsters often ride on an adult’s back. In occasional years, including 2004, some late broods hatch in July, presumed to be from second clutches of eggs, although their success rate is poor.

This species has a well-merited reputation for rapidly colonising, and – just as quickly – abandoning breeding waters, so we should enjoy them whilst we may. The history of the breeding numbers at Woolston, since the time of our First Atlas is shown in the graph.

Concerns are often expressed about the low productivity, averaging only about one chick per pair, but it appears to be sufficient to maintain stable or slowly increasing numbers. Unfortunately, apart from the numbers breeding, very little is known about the population dynamics of the British Black-necked Grebes: How long do they live? When do they first breed? Do the young birds return to the UK? Is it a ‘closed’ population or is there interchange with other European birds? Neither is much known about why Woolston is such a good site for them, and studies of habitat; the density of aquatic invertebrates; the presence of fish (either as predators of chicks or as competitors for food); water chemistry; and predation would help to provide prescriptions for their conservation, both at Woolston and other sites.

Much of the information on the species’ biology comes from work in North America, where the species (known there as the Eared Grebe) is abundant. These birds, however, have some exceptional physiological adaptations that do not apply to European stock – such as reducing their pectoral muscles so much that they could not fly whilst they gorge themselves on brine shrimps at California’s Mono Lake (Ogilvie 2003) – so it is perhaps not wise to borrow much from the American studies.

Breeding was proven at one Cheshire site in 1984 but the species was not mapped in the first Atlas, so no ‘change’ map is presented here.

During the wintering Atlas survey, Black-necked Grebes were recorded in three tetrads, all of them also having breeding season records, and they may well be late autumn migrants rather than truly wintering birds. It is not known where British Black-necked Grebes spend the winter. As nocturnal migrants, they are seldom seen on migration. The species extends as far south as trans-Saharan Africa, and there has been some speculation, from the coincidence of their spring arrival dates at Woolston with the first summer migrants, that the grebes might have undertaken similar journies, from southern Europe or perhaps beyond. On the other hand, Brown and Grice (2005) suggest that it is likely that birds that breed in Britain overwinter in this country. The known numbers wintering in British waters, around 120 birds (Winter Atlas, Baker et al 2006) and thought to contain birds from continental Europe (Migration Atlas), would nowhere nearly account for all of the British breeding stock.

In the BTO Winter Atlas (1981-84) there were records from six 10km squares in Cheshire and Wirral (five records of single birds and one of two together).

Sponsored by Woolston Eyes Conservation Group