Goldcrest © Andy Harmer

The maps show that the range of this, our tiniest bird, has increased greatly since our First Atlas: it is present in half as many tetrads again (417 compared to 280) and was proven breeding in almost twice as many (133 compared to 70). There is nothing in the national statistics to explain the major increase in Cheshire and Wirral. Although the numbers of this species, as a small resident insectivore, are reduced following hard winters such as those of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the national breeding population was higher throughout our First Atlas period than it is now: the English breeding index now is similar to, but somewhat lower than, that during our First Atlas. Indeed, the species is currently on the Amber List of species of conservation concern because its population had fallen by more than one quarter over the period 1975-2000.

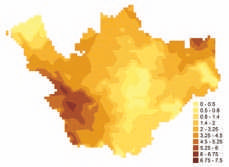

Their expansion has taken Goldcrests across most of the county. Their strongholds are the north-east and south-west of Cheshire, with much of Wirral, and around Chester and Congleton. Birds are found at high densities in the Forestry Commission woods around Delamere and Macclesfield Forests. [They are missing from much of a line running from the edges of the Cholmondeley estate (SJ55L) to Tabley (SJ77D); the industrial and marshland belt across the south Mersey from Ellesmere Port (SJ37Y) to Frodsham (SJ57E); most of Halton in SJ58; and the line of the River Gowy through SJ46 and SJ47.]

Goldcrest abundance.

This is a difficult species to prove breeding, and most records were of possible breeding through observers hearing their high-pitched song (149 tetrads) or finding birds in suitable habitat (45). Probable breeding was scored with records of pairs of birds (59), display or courtship (7), birds visiting a probable nest site (10), carrying nesting material (9), or anxiety calls (5). Most confirmed breeding, in 84 tetrads, derived from observations of recently-fledged young: Ann Pym near Swettenham (SJ76Y) noted that a brood ‘must have just left the nest when we saw them, like tiny balls of fluff’. Fieldworkers in a further 34 tetrads saw adults carrying a faecal sac or food – Goldcrests feeding themselves and their chicks on insects, especially aphids, springtails and caterpillars, and spiders – and records from just 15 tetrads referred to nests (NY, NE or ON). Their nest is difficult to find, a delicate structure of moss, lichens and spiders’ silk, usually suspended beneath a branch of an evergreen tree.

As these comments imply, Goldcrest is indeed the species most likely to be found in coniferous woodland, with the habitat codes from 75 tetrads being given as A2; Coal Tit had 60 such records, but no other passerine was in double figures. Interestingly these are the only two species for which the number of A3 habitat records (mixed woodland, at least 10% of each) exceeds the number of A1 codes (broadleaved woodland), suggesting that, wherever they can find them, Goldcrests preferentially search out the coniferous parts of a wooded area. In 124 tetrads birds were recorded in human habitats and several observers noted comments of ‘conifer in large garden’. They are not solely restricted to conifers, however; indeed, if they were, there would be few Goldcrests in the county because only 1% of the land area of Cheshire and Wirral is coniferous woodland, and only one-fifth of the 1-km squares (585/ 2687) have any coniferous woodland (CEH land-cover survey 2000). Not surprisingly from those statistics, the county holds only a low proportion of the UK breeding population of nearly 1,750,000 birds (Newson et al 2008): the BTO’s analysis of Breeding Bird Survey transects shows that the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral in 2004-05 was 6,140 birds (2,620-9,670), less than 0.5% of the national total.Sponsored by Astra Zeneca, Club AZ Natural History section