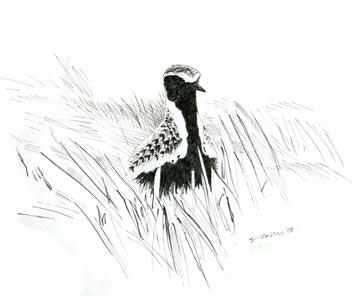

Golden Plover © Ray Scally

Despite concern over their status, and the comment in our First Atlas ‘that this species is clearly endangered as a breeding bird in the county’, Golden Plovers appear to be maintaining their range and numbers in England, although declining significantly in Scotland (Sim et al 2005). Surveys of the South Pennines Moors SPA, of which the Cheshire moors are a part, showed no change between 1990 and 2004-05 in the breeding population of Golden Plovers (Eaton et al 2007). This Atlas map shows that their range has contracted somewhat since our First Atlas, when they were present in 14 tetrads, with breeding confirmed in six of them, but an annual total of only seven or eight territories. They have been lost from six of those tetrads, including four at the northern end of the hills, but were recorded in two where they were not seen twenty years ago. Birds were proven to breed in three tetrads, all in 2006, when adults with chicks were seen on High Moor/ Piggford Moor (SJ96U); in the Shining Tor tetrad (SJ97W) and in the Birchenough Hill tetrad (SJ96Y). Probable breeding records came when agitated adults were found in SJ97V (above Yarnshaw Hill) and near the Cat and Fiddle (SK07A), with birds displaying near the county boundary near Jenkin Chapel (SJ97Y). All of these tetrads are above 350 m in altitude.

In SJ97R, north of Macclesfield Forest, it is not thought that they breed in the tetrad but since 1999 Steve Atkins has noted flocks of up to 28 birds feeding there from April through to July, with birds seen flying in from the east and displaying in flight. These are probably off-duty birds, especially females as males do much of the daytime incubation of the eggs, who fly up to 10 km from their nest to feed in fields rich in earthworms, cranefly larvae and other invertebrates. Such fields are as important to their breeding success as is suitable moorland itself (Brown & Grice 2005).

Golden Plovers have been returning to the Cheshire hills noticeably earlier in recent years, and breeding earlier in warmer springs, although ultimately, the warming climate will probably put an end to their breeding in our area, and they are predicted to be lost completely from England as a breeding bird later this century (Huntley et al 2007). Tipulids are the main food taken by chicks, totalling 60% or 70% of their daily intake, both as larvae (leatherjackets) and adults (cranefly or daddy-long-legs); timing the breeding cycle to coincide with emergence of the adults is important for chicks to grow well. They also eat beetles, spiders and caterpillars, with a few berries. Adults may move their chicks up to 2 km to find better foraging sites, which include bare peat and small marshy areas (Pearce-Higgins & Yalden 2004).

In prime habitat they can achieve densities of 20-30 pairs per tetrad, with nests every 400 m (BTO Second Atlas) but the Cheshire moors are very different. The county bird reports during the 1990s gave annual figures that varied from four to twelve territories. During this Atlas period, John Oxenham thought that there were three pairs in SJ96Y in 2004, and the Cheshire total must be at least six pairs, but a coordinated count would be valuable to arrive at a definitive figure for the Golden Plover population.

Sponsored by Dr J. D. Atkinson