Grey Heron © Richard Steel

Cheshire is the pond capital of Britain, and it is not surprising that it is the heron capital as well. Two of the five largest heronries in Britain are in Cheshire and Wirral, and the county holds more than one-in-twenty of Britain’s birds. The private wood on the north side of Marbury (Budworth) Mere (SJ67N) holds currently the largest colony of Grey Herons in Britain, 180 apparently occupied nests (AON) in 2005, and that at Eaton Hall (SJ45E) – in existence since at least 1874 – is the third largest with 149 nests.

The county’s major heronries are all in tall trees at secluded sites. Grey Herons use a wide variety of species of tree, whichever are tall enough; those recorded in the county since 1980 are Scots pine, Corsican pine, oak, horse chestnut, alder, birch, larch, sycamore, poplar, beech, ash, elm, willow and hawthorn. There can be many nests in the same tree, up to 18 in one alder at Radnor Mere in 1999. They usually nest at heights of 12 m to 20 m or more, and the nests in the tallest trees in the wood are presumably the most desirable because they are the first to be occupied each year. Less usual nesting sites are on or near the ground, as with an odd nest in phalaris/ willow at Woolston in 1999 and 2000, and up to 14 nests in the flooded hawthorn hedges in No. 6 bed deposit lagoon at Frodsham Marsh, where some have been only 1 metre above the water level as pumping operations proceeded, and herons have faced competition from Canada Geese!

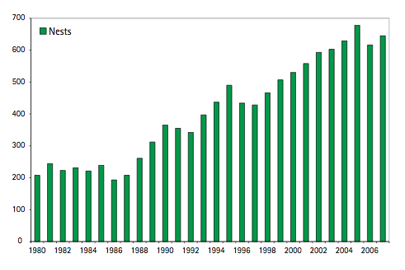

It is believed that all of the county’s heronries are known about and counted annually as part of the national census started in 1928, surveyors going into the woods in April or May, mapping the trees and assessing the occupation of nests: the total of apparently occupied nests in Cheshire and Wirral in the three years of this Atlas was 629, 678 and 616. Nesting numbers in the county have risen substantially in the last twenty years: the mean during the three years of this Atlas of 641 AON is more than three times the low point in 1986 of about 193 AON. The British total of ~10,600 AON in 1986 rose nowhere nearly as sharply, by 27% to 13,430 AON in 2003 (Baker et al 2006). Their numbers are restricted, locally and nationally, by mortality in harsh winters, and the warming climate must have assisted their rise, probably along with a long-term improvement in the aquatic environment. The long-running programme of nest-recording and ringing by Merseyside Ringing Group has shown that, as the county population has risen, the number of chicks fledged per nest has fallen, in a clear example of density-dependence: the Grey Heron population is limited by the carrying capacity of the ecosystem.

The total of apparently occupied Grey Heron nests in cheshire and Wirral,

1980–2007.

The Grey Heron population of Cheshire and Wirral, assessed from the BBS transects in 2004-05, was 3,050 birds (with wide confidence limits of zero to 7,940). The number of breeding adults is about 1,300 so this figure implies more non-breeders than breeders: most Grey Herons do not nest until two or three years of age, so there are large numbers of immature birds present, and BBS fieldworkers might also have counted some early-fledged juvenile birds. The county figure is 4.2% of the national total of 57,220 birds (Newson et al 2008).

Grey Herons breed early, some birds returning to their nests around Christmas, and many are sitting on eggs or chicks during the worst of the winter weather. On the other hand, some, perhaps first-time breeders or others replacing a lost clutch or brood or maybe adults having a rare second brood, may be nesting late in the season and there can be chicks in the nest for almost half of the year, from February to August.

At the top of the aquatic food chain, Grey Herons eat almost anything that they can find, mostly fishing in ditches and ponds; birds nesting in woods alongside lakes seldom seem to fish in the lake itself, and adults can fly at least 10 km from the nest to find food (Lowe 1953). Most feeding is concentrated around dawn and dusk, and chicks get half of their daily intake in the first two hours of daylight. Herons often raid ornamental ponds for goldfish but their staple food in Cheshire appears to be coarse fish, especially perch, roach and sticklebacks, with occasional amphibians and spawn. Birds near the estuaries eat numerous eels.

The Atlas map only shows the heronries. Birds were reported during the breeding season from almost everywhere in the county, but are not mapped. These could be breeding birds foraging for their chicks, immature non-breeders, and early-fledged young herons. Juveniles are not tended by their parents once they leave the colony, although they may return to the nest for supplementary feeds. They can disperse rapidly: an extreme illustration is the bird ringed as a chick in its nest at Budworth Mere on 29 March 1997 that probably fledged during April and by 27 May was found dead on Humberside, 175 km away.

There are some gaps in the map, especially towards the west of the county, where there could conceivably be other birds breeding – Grey Herons can be surprisingly inconspicuous from the outside of a wood – but it is unlikely that many are not known about. Four new nesting sites were discovered during this Atlas survey, each of them holding just one or two pairs.Sponsored by Macclesfield RSPB Members Group