Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus)

Hen Harrier © Norman Richardson

Hen Harriers come down from their breeding sites on the moors of Scotland, northern England and North Wales to spend the winter in the lowlands, especially alongside estuaries and in other open areas with low vegetation. Their diet consists of a wide range of small mammals and birds, but their winter habits are overwhelmingly linked to the abundance of Field Voles; indeed, an American book on the Marsh Hawk, the Nearctic race of this species, is memorably sub-titled ‘The Hawk that is ruled by a mouse’ (Hamerstrom 1986). When hunting, the harriers quarter the ground, keeping an eye on any movement below, then stall and drop onto their prey. They frequently associate with Merlins, sometimes apparently cooperating in flushing small birds, but other times disputing a catch.

Female Hen Harriers weigh half as much again as the males and are able to take larger prey, including rabbits and hares. They are also better able to withstand hard winter weather, so many females stay all year round on their breeding territory in the Scottish strongholds; males tend to move towards the coast. Even amongst the inexperienced birds, most of them do not move far. Detailed wing-tagging studies have shown that 53% of sightings of tagged males and 65% of sightings of tagged females were reported within Scotland during their first winter, these figures rising to 70% and 75% for older birds (Migration Atlas). Thus, the birds that winter in England tend to be males, especially immature birds; first year males move farther south than older, more experienced birds (Etheridge & Summers 2006). There is direct evidence for the origins of some of our wintering birds from reports of wing-tagged birds. First-year males that had been marked as nestlings in the Scottish Borders were seen on Frodsham Marsh in 1996 and on the Dee estuary in 1998, and another wing-tagged bird in 1999 was ‘thought to have originated from the Forest of Bowland’, according to the annual bird report. A first-year female from the North Wales breeding population was seen in winter on the Dee (Etheridge & Summers 2006).

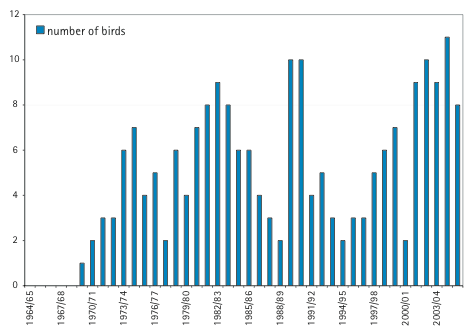

Hen Harrier wintering numbers.

According to the books of Coward, Boyd and Bell, there were about twenty records of Hen Harriers in Cheshire to the early 1960s. The dates of most of them indicate birds passing through, but five or six of them were within our defined winter period. This scarcity continued in the early years of Cheshire and Wirral Bird Reports, from 1964, with numbers gradually increasing during the 1970s, as shown in the bar-chart. A communal roost in Spartina on the Dee estuary was first noted in 1980/81, around the time that many such roosts were discovered (Clarke & Watson 1990), with numbers fluctuating from year to year up to a maximum of seven birds.

Most of the records were on the Dee estuary, on the south side of the Mersey at Frodsham Marsh, and at Risley Moss, with a few scattered observations elsewhere, exactly the picture shown by this Atlas map.

![]() There were no breeding season records during the period of this Atlas survey. In several years they have bred in Derbyshire, with birds occasionally recorded hunting in Cheshire during 1990, 1997 and, notably, in 2003, when a pair was displaying on four dates.

There were no breeding season records during the period of this Atlas survey. In several years they have bred in Derbyshire, with birds occasionally recorded hunting in Cheshire during 1990, 1997 and, notably, in 2003, when a pair was displaying on four dates.

Sponsored by John Wright