Lesser Whitethroat (Sylvia curruca)

Lesser Whitethroat © Steve Round

This is the commonest Sylvia warbler across much of agricultural Cheshire, yet is under-recorded as some observers do not recognise its song. The most obvious component of the song is a loud rattle, a bit like the beginning of a Yellowhammer’s song or the second half of a Chaffinch’s and completely different from any other British warbler; at close distance a weak warble can be heard as well. If some observers find it difficult to detect the species, it can be even more tricky to confirm breeding. More than two-thirds of Atlas records were possible breeding, with just 14% of probable and 18% of records being confirmed breeding. (23 FY, 13 RF, 9 others).

Lesser Whitethroat is the hedgerow Sylvia par excellence. The recorded habitat codes showed 73% in farmland, with 16% in scrub, 6% in human sites and just 2% in woodland, but hedgerows were mentioned in half of the occupied tetrads, over twice the proportion for any other warbler. These records showed a preference for tall hedges (E8) over short hedges by a factor of more than 5:1. The national nest records (Mason 1976) showed that Lesser Whitethroats nest higher than the other Sylvias, most nests at heights of 0.6 to 1.2 m. In southern England, where almost all of the nests were recorded, 40% were in hedges, 34% in scrub and the rest in woodland, parkland, etc. They used hawthorn and blackthorn much more than other warblers, also favouring bramble and rose, not just for nesting but also finding their breeding season diet of small soft-bodied insects and their larvae by diligent searching through the shrubs.

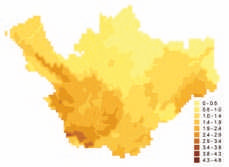

The abundance map shows the highest densities in the southwest of Cheshire and along the Wirral peninsula, and the estimate of the county’s breeding population in 2004-05 is 3,480 individuals (1,510-5,460), an average of about 13 birds per occupied tetrad. Thus, the county holds about 3.4% of the English population; for a species with a traditionally south-easterly distribution, it is surprising that we have more than our proportionate share of their population. An indication of its range is well illustrated by the figures for the atlases of nearby counties: presence in 37% of tetrads in this Atlas, 16% in Lancashire and North Merseyside (1997-2000) and 5% in Cumbria (1997-2001). This is not just a simple effect of geographical range, however, as Lesser Whitethroats are seldom found anywhere above an altitude of 200m.

Lesser Whitethroat abundance.

This is one of the few species that migrates in autumn to the south-east, Lesser Whitethroats wintering south of the Sahara in eastern Africa, mostly at low altitudes in Ethiopia, Sudan and Chad. Thus, they have not been subject to the drought in the Sahel that has impacted many migrants in western Africa, and also appear not to have been affected by the well-publicised periods of drought that have afflicted humans in Ethiopia and Sudan: annual fluctuations in their population are not correlated with African rainfall. A recent paper by BTO and RSPB staff (Fuller et al. 2005), however, suggests that pressures during migration and in winter are the most likely causes of the decline in the national population indices, which peaked just after our First Atlas, in 1986, and have dropped by 35% in 18 years from then to 2004.

Sponsored by Tony Usher