Mistle Thrush © Sue & Andy Tranter

By contrast with our two other common breeding thrushes, Mistle Thrushes are considerably less widespread than in our First Atlas, being found in 48 fewer tetrads. The losses have been scattered across the county, but most noticeably in the centre and south of Cheshire where there are now some obvious gaps without the species, as in SJ46/ SJ56/ SJ66/ SJ65/ SJ64. This is mostly classical pastoral Cheshire and this is one bird that ought to have benefited from the switch from hay to silage, the earlier grass-cutting exposing a sudden flush of invertebrates that fits well with the Mistle Thrush breeding season (O’Connor & Shrubb 1986) but there must be something else in modern agricultural practice that is inimical to these birds.

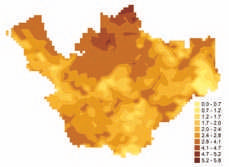

Mistle Thrushes are only ever found at relatively low densities: they defend large territories, usually at least 1 ha and some more than 10 ha (Simms 1978), that contain a variety of habitats. Analysis of the submitted habitat codes for this Atlas shows that most birds were in farmland, broadleaved woodland and human sites. This is the archetypal bird of ‘parkland’ – open, grassy areas with mature trees. Compared to Blackbirds and Song Thrushes, Mistle Thrushes are more likely to be found in agricultural grassland, including unimproved grassland (especially in the hill country), and much less likely to frequent scrub or farmland hedgerows. They were recorded in 207 human sites, 100 of them urban or suburban habitats, and Mistle Thrushes can breed even in the most built-up settings, provided that there are sufficient lawns and flower-beds to provide food. The abundance map suggests that the highest concentrations of Mistle Thrushes are in the most populous north of the county.

Mistle thrush abundance.

Most of the confirmed breeding records came from observers seeing adults carrying food (157 tetrads) or with recently-fledged young (155), with nests found (NE/ NY/ ON), usually in the fork of a tree and often high off the ground, in 68. Some of the probable breeding codes could, with luck, have been converted to proven breeding: in 16 tetrads observers found birds visiting a probable nest site or carrying nesting material, and 22 tetrads provided fieldworkers with ‘A’ – agitated behaviour or alarm calls – this being one of the more demonstrative species. Some territories are difficult to locate, not least because Mistle Thrushes will fly a long way, up to 1 km on occasions, if a prime source of food becomes available such as a ploughed field or newly-mown pasture or playing field (O’Connor & Shrubb 1986). Others can seem ridiculously easy to find, especially if an adult ‘churrs’ noisily and flies off with a beak full of worms, or a Magpie goes too near to the nest, when ferocious attacks by the thrushes usually deter them from plundering the nest. Despite their being early nesters, often starting in March before there is much vegetation on the trees to conceal them, data from the BTO’s nest record scheme show that the success rate of Mistle Thrush nests, with eggs or with chicks, is much higher than that of Blackbirds or Song Thrushes.

Nationally, Mistle Thrush populations have declined significantly since the mid 1970s, especially on farmland, causing them recently to be added to the Amber List of species of conservation concern. The drop has been mostly on farmland rather than woodland areas (Brown & Grice 2005) and the decline is likely to have been driven by reduced annual survival (Siriwardena et al 1998). The national population index fell by 16% during the seven years of our First Atlas, and is still dropping, with the 2004 figure 25% lower than that of 1984. In Cheshire and Wirral, the BTO BBS analysis shows that the breeding population in 2004-05 was 6,240 birds (4,190-8,290), corresponding to an average of about 13 birds per tetrad with confirmed or probable breeding, or 11 birds per tetrad in which the species was recorded.

Sponsored by Cynthia Johnson