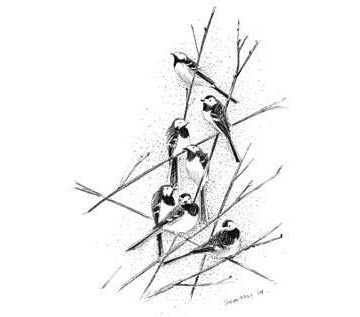

Pied Wagtail © Ray Scally

Pied Wagtails feed on insects all year round and have to be adaptable to achieve this. Some of our birds, especially the adults, stay close to their breeding areas while others, and many youngsters, move south, some as far as the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, our wintering population is augmented by arrivals from the north of some Scottish birds (Migration Atlas). They also retreat from the highest ground, and this is just evident in a few tetrads at the east of our recording area where they quit nine tetrads where they bred above 300 m. They appear to be missing from some of the most open areas at sea level as well: the Dee and Mersey saltmarshes, and parts of the Mersey valley mosses. Otherwise, the winter distribution is similar to that for the breeding season.

This map would surprise the earlier chroniclers of the county’s birds. Coward and Oldham (1900) knew the Pied Wagtail as a partial migrant, ‘only a few birds remaining through the winter’. In contrast to the present day, they commented that, especially during a frost, Pied Wagtails are numerous on the Dee marshes; the birds feed along the high water mark and resort to the gutters when the tide is out. Boyd (1951) mentioned ‘the comparatively few Pied Wagtails that winter here’, and Bell (1962) wrote that ‘relatively few birds remain through the winter’ and that ‘the numbers in most areas in winter are very small and widely scattered’. Unfortunately, the annual county bird reports give no indication when Pied Wagtails changed their winter habits to become common and widespread, as now. From 1964 to 1977 there were only three winter records published, two of feeding concentrations at sewage farms and one of a December roost in Wilmslow. A roost at Rolls-Royce, Crewe, drew comment in 1978 to 1980, then fieldwork for the national Winter Atlas (1981/ 82 - 1983/ 84) focused the attention of some observers. Pied Wagtails were found in all forty of the county’s 10 km squares, although one-third of them only registered the lowest (1-7 birds) category of abundance. In the cold winter of 1981/ 82 they were noted as being much more localised in rural areas than during the breeding season. From then on, winter records were published annually, mostly of totals at sewage farms and roosts and by 1992, when the annual bird report introduced a summary status line, the species was described as a ‘common widespread resident’, meaning 1,000 – 5,000 birds in winter. Pied Wagtails are susceptible to freezing weather, and presumably the milder winters since the late-1980s have allowed them to survive in the county.

As well as continuing to inhabit farmland, especially grassland and farmyards, wagtails move into gardens, and the Pied Wagtail is perhaps the most characteristic bird of sewage treatment plants, where insects are guaranteed. The winter habitat codes showed most birds (49%) in human sites (5% urban, 11% suburban and 33% rural); 41% on farmland, mostly grassland, and 7% spread across all types of freshwater types. Flying insects are scarce in winter, so their diet becomes beetles, spiders and invertebrate larvae, supplemented by occasional small seeds and breadcrumbs in human sites. They tend to flock in winter, but some, mostly males, establish linear territories alongside suitable watercourses. In midwinter, they spend 90% of the daylight hours feeding, taking an average of 18 items per minute. This feeding rate – one small insect every 3 or 4 seconds throughout a winter’s day – seems incredible but is only just sufficient for a bird to gain enough energy to sustain it through the night (Davies 1982). Perhaps in line with this territorial tendency, most birds were reported during this winter Atlas in ones or twos, but there were some large flocks in favoured feeding sites including eight feeding flocks of over 100 birds, including two each at sewage works and wet stubble fields.

This species is renowned for its urban winter roosts, birds gathering either on the flat roofs of large buildings, which presumably are warmer than the surrounding areas, or in dense evergreen bushes, with Laurel especially favoured, although sometimes wagtails roost on the bare branches of trees. Examples were reported during this Atlas of roosts in the town centres of Runcorn, Crewe, Alsager, Wilmslow and Macclesfield. They also have a liking for large building complexes in a mainly rural environment such as motorway service areas, Alderley Park, Daresbury Laboratory and Cheshire Oaks. Several of the larger roosts may number in three figures, with counts submitted of up to 300 in the regular roost around Crewe railway station (SJ75C), up to 200 in Macclesfield town centre (SJ97B) and 120 outside Runcorn Police Station (SJ57K) in January 2005. Their autumn reedbed roosts are seldom used into the winter period, presumably because they are too exposed for the long cold nights.

Birds of the nominate race, White Wagtails Motacilla alba alba, pass through on spring and autumn passage between their breeding grounds in Iceland and their normal wintering quarters in west Africa. In recent years a few have been noted in winter in Britain, including one during this winter atlas, a bird ringed at Prestbury Sewage Farm SJ87Z in winter 2005/ 06, with another possible White Wagtail seen in SJ37W.

Sponsored by Norman Scott