Skylark © Richard Steel

The Skylark has become an icon for the effects of industrialised agriculture on our wildlife, so it is depressing to see the extent of loss of this species between our two Atlases. The change map shows Skylarks lost from 172 tetrads, with 17 gains. To put it another way: in 1978-84, there were only 39 tetrads in which the species was not found; in this Atlas, there were 185 blank tetrads. Most of the losses are scattered across agricultural Cheshire, and the distribution map shows several significant gaps, such as the east of SJ87 and the west of SJ46, where Skylarks were present in every tetrad twenty years ago; birds were already patchily distributed in SJ37 in the First Atlas, now an obvious blank area. The species has also abandoned Hilbre and most urban areas such as Chester, Ellesmere Port, Northwich, Runcorn and the east Wirral conurbation, although odd birds breed nowadays in derelict brownfield sites in the Birkenhead docklands.

The habitat codes showed, unsurprisingly, that 81% of records were on farmland, with the main categories 33% improved grassland, 15% unimproved grassland, 16% mixed grassland and tilled land and 12% tilled land, so disproportionately high use was made of unimproved and mixed farmland, plus 11% of records on semi-natural grassland and marsh. On improved grassland, high fertilizer applications have led to vegetation that is too tall and dense for nesting, as well as high nest failure rates through trampling by cattle or frequent mowing for silage. Skylarks’ ground nests suffer high levels of predation, which they minimise by nesting far away from field edges and having the shortest incubation period of all British birds (11 days), with chicks scattering from the nest about 8 days after hatching, well before they can fly. The 79 broods that I have ringed in Cheshire, mostly at Frodsham Marsh, 1981 to 2007, had hatching dates from 4 May to 12 July. They normally lay a clutch of 4 eggs, reducing with later attempts: I found a mean brood size of 3.5 chicks in May, 3.4 in June, and 2.9 in July. Skylarks are not choosy about the food they bring to their chicks, taking whatever invertebrate prey is abundant in the area. Adult Skylarks carry large items of food for their chicks, often visible from a distance with the naked eye, and males sometimes sing with a beak full of food! Some Atlas surveyors found the species frustratingly difficult, and many observed just song, although some recorded it as D – display, accounting for the high proportion of ‘probable’ breeding.

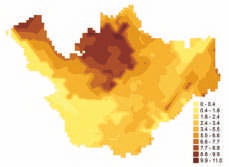

Skylark abundance.

The national population index dropped by 40% during the fieldwork period of our First Atlas, 1978 to 1984, and has fallen by another 32% in the twenty years since then. Cheshire can never have been one of the most important counties for Skylark, however, as improved grassland holds the lowest Skylark density of all habitat types (Browne et al 2000).

The BTO BBS analysis for 2004-05 shows that the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral was 9,010 birds (4,880-13,130), corresponding to an average of about 19 birds per tetrad in which the species was recorded. Probably most of the birds detected on BBS transects are the singing males, so these figures are likely to equate roughly to numbers of pairs. Densities vary enormously across the county, as suggested by the abundance map. In many tetrads, especially in south Cheshire, it was a struggle to find even one Skylark, while some tetrads in the eastern hills, and on Frodsham Marsh, held 20 or more pairs. On the Dee estuary saltmarsh, Skylark breeding densities reach the very high levels of around 120 pairs per km2 (~500 pairs per tetrad) on ungrazed or moderately grazed coastal marshes, but fall to 52 pairs per km2 on heavily grazed marshes (Colin Wells, quoted in Donald 2004).Sponsored by Chester RSPB Group