Swift (Apus apus)

Swift © Mike Atkinson

The First Atlas text concluded with the words ‘a good census of the county’s Swift population would be valuable’. This challenge was accepted by Brian Martin, who led such a project in 1995 (Martin 1997). Swifts are difficult birds to survey. Their normal daily feeding flights probably take them over every tetrad in the county, and they will feed at least 100 miles away from their breeding sites when a summer storm has concentrated their insect prey (Bromhall 1980). Thus, records of birds seen are meaningless for an Atlas of breeding birds, and this Atlas maps just confirmed breeding and birds visiting probable nest-sites (N).

Apart from at their breeding sites, Swifts spend their entire lives – awake and asleep – on the wing, catching nearly all types of flying insects, from minute thrips to large hoverflies, and spiders whisked into the breeze. They feed up to several thousand feet high in the air, and it is often difficult for ground-based observers to see them with the naked eye. On a fine day a pair of Swifts feeding young may catch some 20,000 insects and spiders.

Swifts winter south of the equator in central and southern Africa. They mostly return here in early May, and are conspicuous by their fast flight, and their noisy, screaming flocks. Their ancestral nest sites are probably in trees and caves, but nowadays Swifts entirely depend on man, with their nests exclusively in buildings, mostly houses. They enter the roof space through small gaps under the eaves, and sometimes between tiles. The 1995 survey showed that almost all nests are in properties over 40 years old. Especially favoured are the 1930s council estates and old Victorian and Edwardian houses, and birds are extremely loyal to traditional nesting sites, some of which have held Swifts for the whole lifetime of their human residents (Martin 1997). Not only is the species faithful to established sites, but my study at the colony in Cotebrook church has shown that most adults use exactly the same nest-site from year to year.

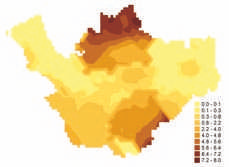

Swift abundance.

The distribution map illustrates clearly the correlation between Swifts and conurbations, and their avoidance of the heavily wooded areas. Despite the comments about site-fidelity and stability in a long-lived bird, the maps show substantial changes from the First Atlas. There have been gains in urban Wirral, where the species is almost ubiquitous, and around their other strongholds of Warrington, Middlewich, Crewe and Macclesfield, with an intriguing line of new records running north-south to the east of Tarporley. There has been a serious drop in the Chester area and west Cheshire in general, and east of Runcorn and south of Crewe. Much of this appears to have occurred in the decade between the First Atlas and the 1995 survey, for the changes from the 1995 survey to this Atlas are less dramatic, but include large-scale losses around Chester, with smaller losses around Northwich, Crewe and Macclesfield.

The 1995 survey found an estimated county total of around 6,500 Swifts (Martin 1997). Almost half of them were in four areas – Crewe, Warrington, Chester and the east Wirral conurbation from Ellesmere Port to Wallasey. It is impossible to translate that figure into pairs, mainly because of unknown proportions of incubating birds and non-breeders prospecting for nest-sites. Using a different methodology, the BTO analysis of BBS returns, the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral in 2004-05 is estimated at 4,300 birds (with very wide statistical confidence limits from zero to 8,660). Swifts are not well monitored by any BTO survey and their conservation status is unknown, although repeat surveys in other counties have revealed significant drops, often attributed to a reduction in nest sites in modern buildings and renovation of older properties (Brown & Grice 2005). A local census of southeast Cheshire in 2001 showed a 38% drop in population from 1995/ 96, with almost every colony showing a decline and the massive west Crewe (SJ65Y) colony down from 450 nests to 120 (Lythgoe 2001).

Sponsored by Christian and Sue Heintzen