Whitethroat (Sylvia communis)

Whitethroat © Richard Steel

‘Where have all the Whitethroats gone?’ was the plaintive cry in 1969, and the title of a famous paper giving the answer (Winstanley et al 1974), following the massive crash in population that first alerted us to the importance of drought in the African Sahel for our wintering birds. But they have bounced back and, although nowhere nearly as common as it was in the 1960s, Whitethroat is again the most abundant warbler in Cheshire and Wirral. The BTO BBS analysis shows that the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral in 2004-05 was 16,890 birds (10,410-23,380), corresponding to an average of 44 birds per tetrad with confirmed or probable breeding, or 31 birds per tetrad in which the species was recorded. In prime habitat they can be remarkably numerous, exemplified by the record total of 185 singing males found across 260 ha of SSSI at Woolston in the 2006 census there.

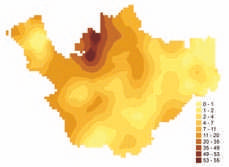

They are obviously still vulnerable to conditions on their wintering grounds, mostly in Senegal and Mali just south of the Sahara, and annual fluctuations in their abundance are closely linked to their overwinter survival and Sahel rainfall (Baillie & Peach 1992). The national population index was at its lowest at the end of our First Atlas period, following another failure of the African rains in autumn 1983, but their numbers have risen ever since, and had more than doubled by 2004. This rise in population has been accompanied by a spread in distribution, with presence recorded in a net 42 tetrads more than in the First Atlas, but with a patchy picture of 100 gains and 58 losses. The ‘change’ map shows areas of considerable gains in the southern and eastern parts of Cheshire, as well as towards the north of Wirral: they are still not that common in the south of the county, where they are often outnumbered by Lesser Whitethroats, and the abundance map shows the highest concentrations of Whitethroats in Halton and the Mersey valley. The national Atlases, recording 10x10 km squares, show that they avoid the highest land, above about 300 m, but the finer detail of our Atlas suggests that they are scarce above about 100 m, albeit with some scattered records to the east of that contour. 51% of habitat records were from farmland, with 29% scrub, 6% woodland and 7% human sites. They readily move into built-up areas provided that there is a suitable area of overgrown land, typical post-industrial ‘brownfield’ sites being ideal. This is one of the few species that appears to flourish in low, heavily-trimmed hedges, provided that there is some ground vegetation present, so they have perhaps not been hit as badly as some others by agricultural intensification, although obviously they would not tolerate complete removal of hedgerows (Lack 1992).

Whitethroat abundance.

Early in the season, the males are conspicuous, often singing from the top of a bush and performing song-flights. Even when hidden from sight, their song is loud and distinctive; descriptions of their song always seem to include the word ‘scratchy’. They nest close to the ground in nettle, grasses or a suitably impenetrable bush, the female laying 4 or 5 eggs from mid-May, with some having second broods in July. When they have young, they draw attention to themselves with their insistent buzzing call, and they are easy to see in a hedge with a beakful of insects (167 FY), this species yielding the highest proportion of confirmed breeding amongst the warblers. Observers in 77 tetrads found broods of recently-fledged young, also conspicuous and noisy.

Sponsored by Tricia and Mike Thompson