Yellowhammer © Steve Round

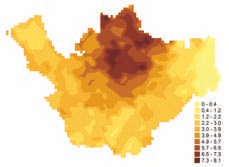

Some see this as a typical species of the Cheshire plain, hence the choice of Yellowhammer for the front cover of this Atlas. To others in the county, however, it has become a scarce bird since it was almost ubiquitous in our First Atlas. The ‘change’ map shows the species lost from 222 tetrads, with scattered gains in just 22. There have been two main components to the changes in the last twenty years: Yellowhammers have been lost from the urban fringe, especially around Macclesfield and Congleton, Halton and the Wirral; and very few are now present in the breeding season above an altitude of 100m. The abundance map shows that the main density of Yellowhammers is around Warrington and the centre of the county.

In many tetrads where they were present, Yellowhammers took a little bit of searching for, as they seldom seemed to be close to habitation or roads. Several fieldworkers commented that they were pleased to discover them quite close to their home, not having realised they were there until they had to survey the area for this Atlas. Their insistent song ‘little-bit-of-bread-and-no-cheeeese’ is far-carrying, usually audible one or two fields away. ‘Song’ accounted for most of the possible breeding records, but adults feed their chicks on invertebrates, carried in their bill, and make obvious ‘tuck’ alarm calls, so FY records provided most of the confirmed records; only one nest was reported in this survey, however, in Delamere (SJ57Q) by the author. Two or three nesting attempts are possible during the season running from April to August; unusually for a passerine, later nests tend to be more successful.

More than 80% of the submitted habitat records were farmland, and observers in almost half of the tetrads added a code of E8 or E9, indicating the importance of hedgerows to this species. They nest on the ground in field edges or ditches, or low down in hedges. Yellowhammers also use woodland edge, scrub and new plantations but these are sub-optimal habitat; they quit the clear-felled areas within Delamere Forest during the 1990s.

Yellowhammer abundance.

Yellowhammer was the last species to succumb to the 20th century agricultural revolution: their national population figures held up for longer than for other farmland seed-eaters, uniquely remaining stable throughout our First Atlas period, with most of their drop coming from the late-1980s to mid-1990s (Siriwardena et al 2000), leaving the national index in 2004 at just under half of its value in 1984 and warranting their position on the Red List of species of conservation concern. This difference in timing from other species suggests that Yellowhammers have been affected by different aspects of the countryside changes, although the reasons are not understood (Brown & Grice 2005). They may well be connected with the increasing specialisation of agriculture and the demise of mixed farming. We do not know, but it is likely that Cheshire’s Yellowhammers have suffered more than most, because detailed study showed that farms dominated by grass and non-cereal crops were most likely to have lost territories (Kyrkos et al 1998). Even small amounts of arable land, perhaps only one field per farm, in an otherwise grassland landscape, are all that they need to maintain a presence (Robinson et al 2001).

The BTO analysis of 2004-05 BBS data gives the breeding population of Cheshire and Wirral as 7,740 birds (7,110-8,370), corresponding to an average of about 32 birds per tetrad with confirmed or probable breeding, or 21 birds per tetrad in which the species was recorded. This figure is only 0.3% of the UK total, the lowest proportion for any of the farmland passerine species, another intimation that our increasingly specialised pastoral landscape is not, nowadays, prime Yellowhammer country.

Sponsored by Frank Gleeson